The Early Years

Bob Willoughby was born in Grundy Center, Iowa on 6 June 1921. His mother’s family was of German and Swiss ancestry. Bob’s maternal grandfather, as a younger son of a well-to do family, inherited nothing and emigrated to the USA with his wife when they were in their late teens, where he became a farmer. Grundy Center was a largely German community where at least one church had services entirely in German. Bob’s father’s family, which is of English extraction, emigrated to America from Nottingham in the early eighteenth century.

His great-great-grandfather had been a preacher in New York State. His grandfather farmed in Iowa, at a time when a farmers did not have a great life expectancy. He retired at the age of fifty, thinking he might live to sixty, but he lived to ninety-four. Bob remembers him. ‘He was born in 1834. When the American Civil War started in 1861 he was considered too old to fight!’

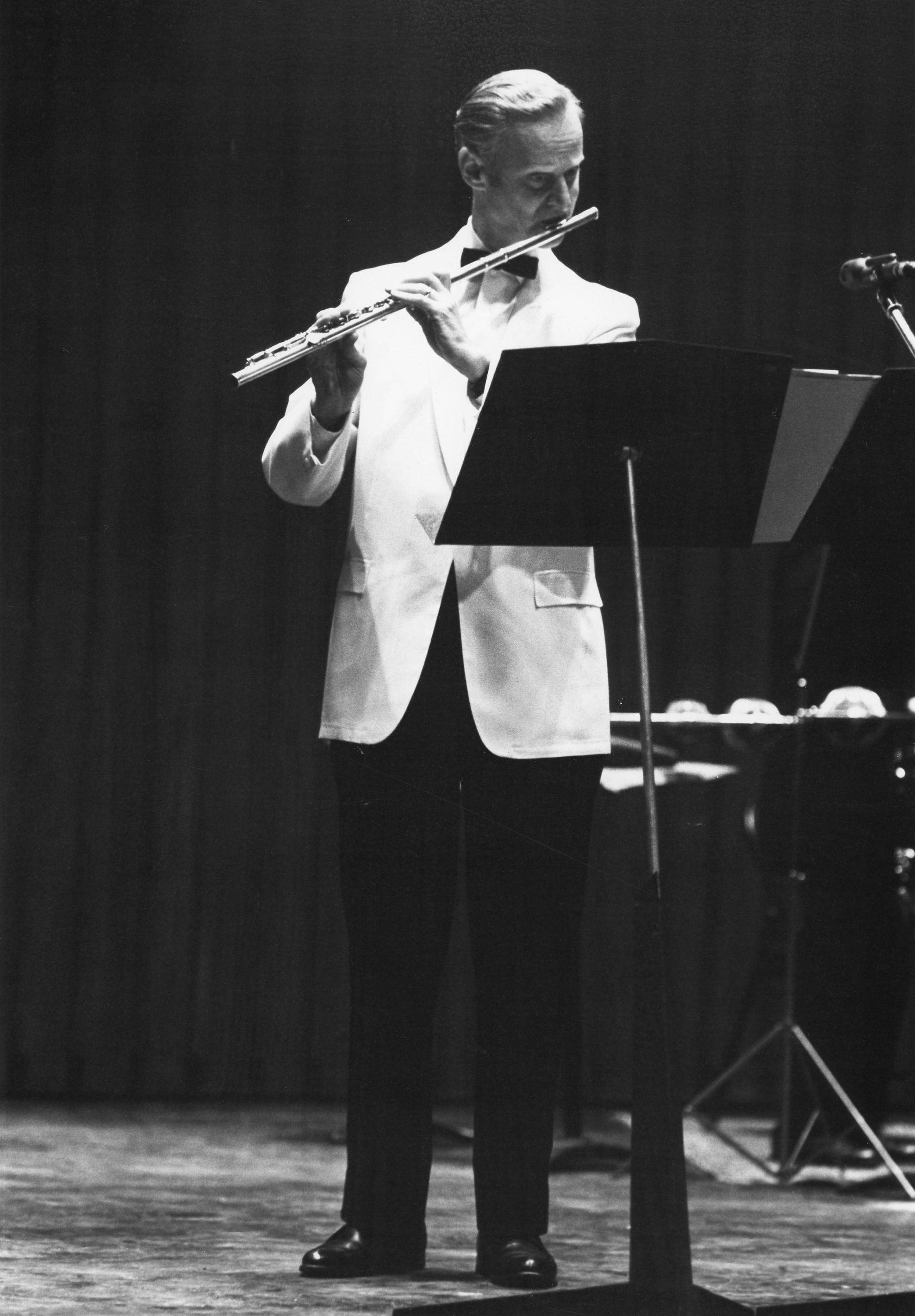

Bob’s father was a lawyer, and Bob was expected to become a lawyer himself. In the fifth grade, aged about ten or eleven, he began to play the flute. There was no flute teacher at his school—he was taught by band directors—but he did have an excellent mentor who was an oboist. It was not until after he left high school that he had a flute lesson. He then went to the famous summer school at Interlochen. ‘That was in fact my downfall in terms of becoming a lawyer,’ he says. ‘I was there two weeks and I thought, I'm in heaven. I fell in love with music and I've been in love ever since.’

While at Interlochen, the head of the Eastman School of Music came through for a visit and, after hearing Bob, offered him a full scholarship to study at Eastman. ‘I was still not sure about a career in music,’ he says, ‘but I loved Eastman. It was the best move I ever made, apart from marrying my wife.’He started at the Eastman School of Music in 1938, where his teacher was the great Joseph Mariano. ‘ Mariano was a nice man,’ remembers Bob. ‘He had a huge sound, and he played really beautifully.’ Mariano, who only died in 2007, was at the time still in his twenties. It is said that he repeatedly refused the first flute job in the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Bob’s time at Eastman ended after four years, at which time the USA entered the Second World War. Bob graduated in 1942, and American had just joined WW2.

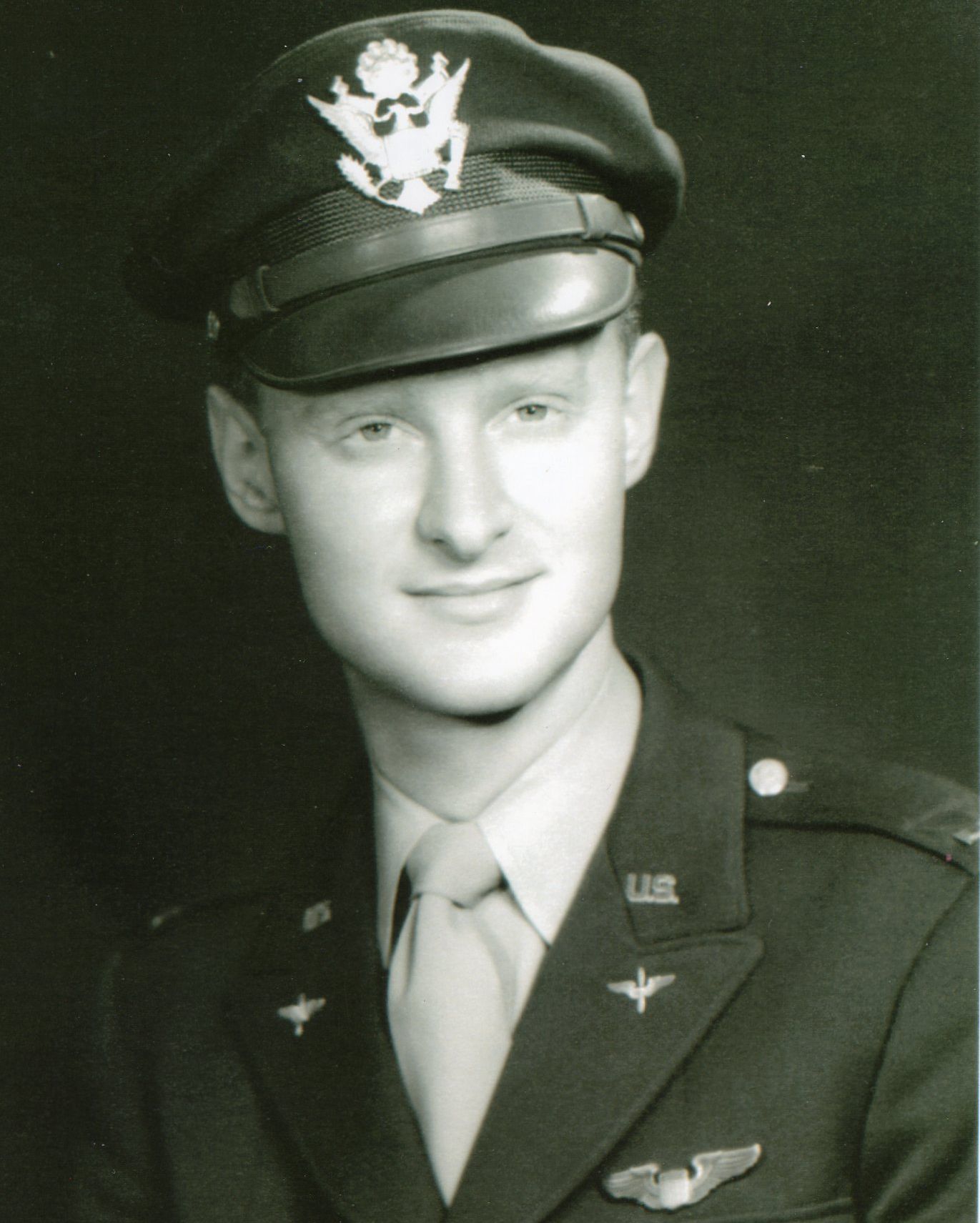

WWII

He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1942, was put in the reserves and in February 1943 began his training as a B24 bomber pilot. ‘I thought every joy I had for music would disappear if I went into a military band!’ he said. ‘I had always been athletic, so I thought I could fly a plane, although I had never done it.’ He had his basic training in the USA, then sailed as part of a convoy to Britain, where eventually he was posted to an airbase in Bungay, Suffolk.

‘I flew my first mission on my birthday,’ he remembers. That day, 6 June 1944, of course, was D-Day. ‘I guess I had a certain amount of anticipation, but that was what we called a milk run, when we just flew across the Channel and straight back again. It was quite safe, really. The second mission was different because we bombed an airport further afield. I always remember seeing a sky full of fighter planes, and I had heard that they would attack bombers when they were over their target. I have to admit that I was really scared, but it turned out they were our fighters. I didn’t know that at the time, but that was the most frightening mission I ever had, because I didn’t know what to expect.’

He flew thirty-five missions in all, mostly over France and Germany, with only one almost ending in disaster. ‘We had just flown across the Channel when two engines failed—fortunately on opposite sides. We dumped everything we could into the sea and headed home. We had just reached the runway when a third engine failed. We were very lucky that day.’ Bob’s wife, Mac, remembers visiting Bungay with Bob many years later. ‘He stood at the end of the runway and for a few seconds turned as green as the leaves.’

Bob was awarded The Distinguished Flying Cross "for heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial flight", and 4 times was awarded the The Air Medal "for single acts of heroism or meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flight".

New England Conservatory

At the end of the war, after his discharge, Bob returned to America and took up his flute again. He had not touched it for some years. He got a place as a graduate student at the New England Conservatory in Boston, where he studied with Georges Laurent, the first flute in the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Laurent had studied with Philippe Gaubert and Paul Taffanel at the Paris Conservatoire.

‘Laurent made me work my tail off. I practised four or five hours a day and made as much progress in one year as I had in four years at Eastman,’ Bob remembers. Laurent was very demanding. ‘I still remember one time I had worked very hard on everything he had asked me to do, except for one thing. Of course, that was the thing he asked me to play. “What’s the matter—haven’t you been practising?” he asked. He really gave it to me! Everything else went well, but I left the lesson feeling really down and told myself that was never going to happen again. That was a good lesson.’

He received his Masters from The New England Conservatory in 1949.

Cleveland, Oberlin, and Cincinnati

After a year in New England, in 1946 Bob got a job as assistant principal flute in the Cleveland Orchestra, one of the best in America. As assistant principal he doubled the first part in some concerts and played first flute in others. The conductor was George Szell, a famed martinet. ‘He was not hail fellow, well met,’ says Bob. Szell was a stern disciplinarian but a wonderful musician. ‘I admired him greatly, but you could never love this guy. When he arrived in Cleveland he did some housekeeping—he fired about twenty people, but, in his defence, they were mostly people who would not have got in normally, except for the war.’ The first flute at the time was Maurice Sharp, who had been there for ten years already when Bob arrived. Maurice Sharp remained as first flute in the Cleveland Orchestra for about half a century. Bob stayed in Cleveland for nine years, leaving in 1955 to focus on teaching.

For the last six years, beginning in 1949, he also worked at the Oberlin Conservatory, where he taught for sixteen or seventeen hours a week. ‘That was a killer. After nine years I quit the orchestra and quit Oberlin, too, except they talked me into going full-time.’ He had been offered the first flute job in another orchestra, which was not as good as the one in Cleveland, but he says he was worn out by the combination of work.

He taught at Oberlin full-time until 1986, apart from a year in 1960 as first flute in Cincinnati under Max Rudolf, which he took because he wanted the fun of playing first flute. He liked Rudolf and got along fine, but says he once sat in the orchestra playing a Brahms symphony that he had played many times before and thought, ‘I don’t want to spend the rest of my life doing this.’ Oberlin made him a good offer, so he returned as a full-time professor. ‘I think I did the right thing. I got to do a lot of chamber music at Oberlin, and I love teaching.

At Oberlin he was the first Robert Wheeler Chair in performance. He was also a member of the Smithsonian Chamber Players. Prominent contemporary composers including Easley Blackwood and Thea Musgrave have produced commissioned works for him. In 1986 he ‘retired’ from Oberlin, but not from teaching of course.

After a year sabatical in London in 1970, Bob acquired a passion for early Baroque music. Bob was a founding member of the Oberlin Baroque Ensemble, and acquired a number of baroque flutes for use in his own performances.

During this time he was also involved in a number of summer programs. He performed as solo flutist of the Festival Orchestra and teacher at the Congregation of the Arts program at Dartmouth College during the eight week summer sessions from 1967-69. Since 1948 he had also spent many summers playing in the orchestra at the Wentworth by the Sea - a grand old New England resort hotel at the time.

Peabody

Years earlier, Bob and Mac had bought a plot of land on the island of New Castle, New Hampshire, just off Portsmouth. They decided to build a house on the land and spend more time in New England. Mac was living there most of the time while their new house was being completed, and Bob stayed in Oberlin, which was far from an ideal arrangement. After 37 years at Oberlin he began to think of moving on.

Bob had been asked to judge a competition at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore, where changes in staff had led to a flute position becoming available. He was offered the job, which allowed him to live in New Hampshire and commute once a week to teach for twelve hours. He accepted the job in 1986 and enjoyed it for the next ten years.

Bob and Mac would often fly down to Baltimore together and spend part of the week there while Bob taught, and then fly back home to New Castle for the rest of the week. This let them spend some time in their peaceful New Castle setting, and some time in the more bustling Baltimore/Washington area with many culutral events and resources. In 1996 however, at the age of 75, the weekly commute began to lose it's appeal and he left Peabody for an opportunity closer to home.

Longy

In 1996 he was offered a job at the Longy School of Music in Cambridge, MA, commuting distance from the house in New Hampshire. He agreed to teach for five hours a week, and although gradually cut his time down to two hours a week he continued teaching up until his death in 2018.

While at Longy, Bob and Mac (and later just Bob) would usually come down to Cambridge on Thursdays and stay at the Sheraton Commander, right across from Longy. He would teach on Thursday and Friday and then they would head home to New Castle on Friday. This gave them the opportunity to go to events in town and have dinner with friends so it really worked out well all around.

In 2001, for his 80th birthday, students from around the world commissioned John Heiss to write Apparitions, which was premiered at a gala concert in his honor at the Longy School of Music.

In 2008 he was presented with the "George Seaman Excellence in the Art of Teaching Award" from Longy. This award celebrates the Longy faculty's devotion to students, artistry, and originality; its ability to inspire students' growth; and its dynamic involvement in the life of the school.

Shortly into the spring semester of 2018, Bob became ill and passed away on March 27 at the age of 96.

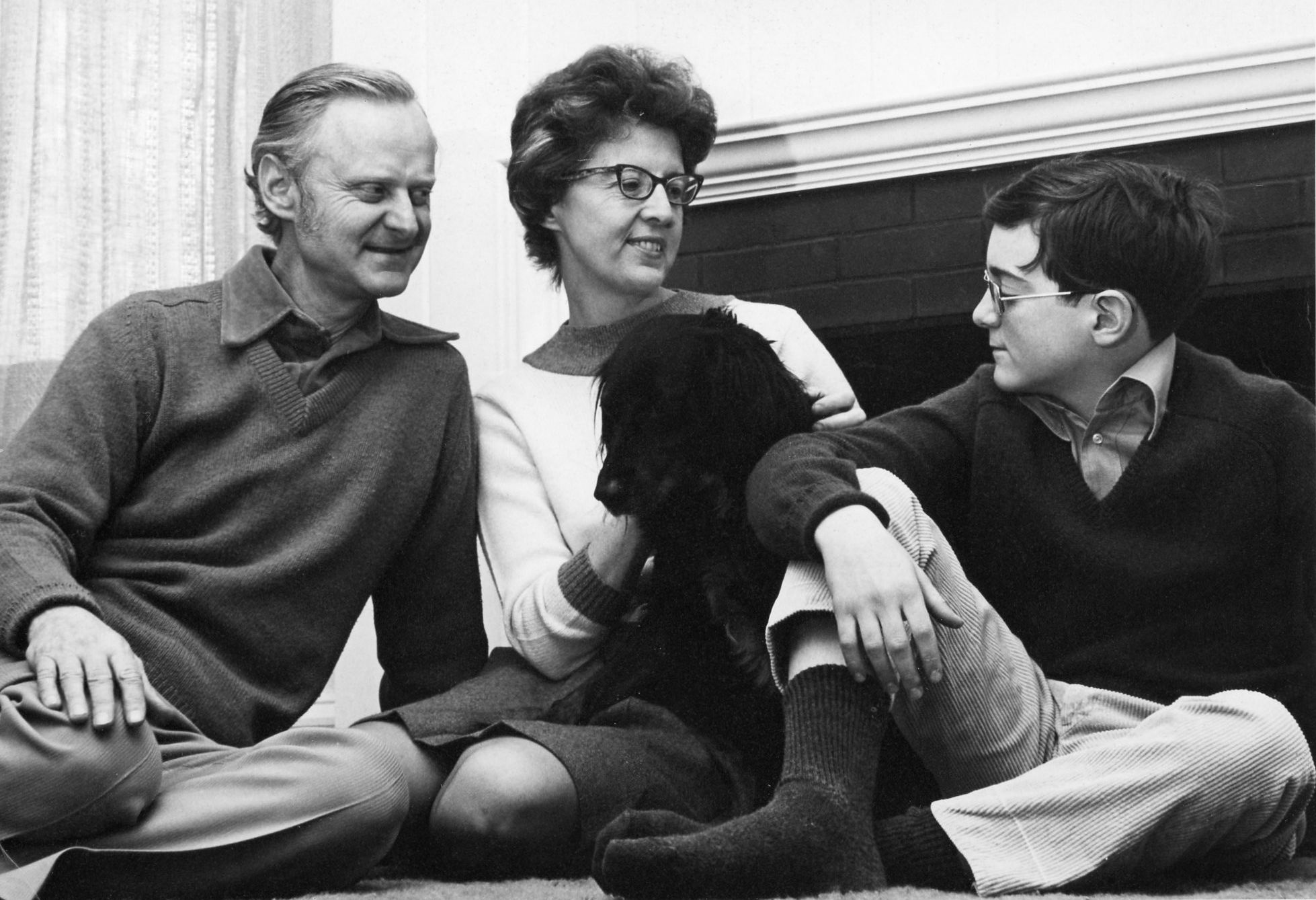

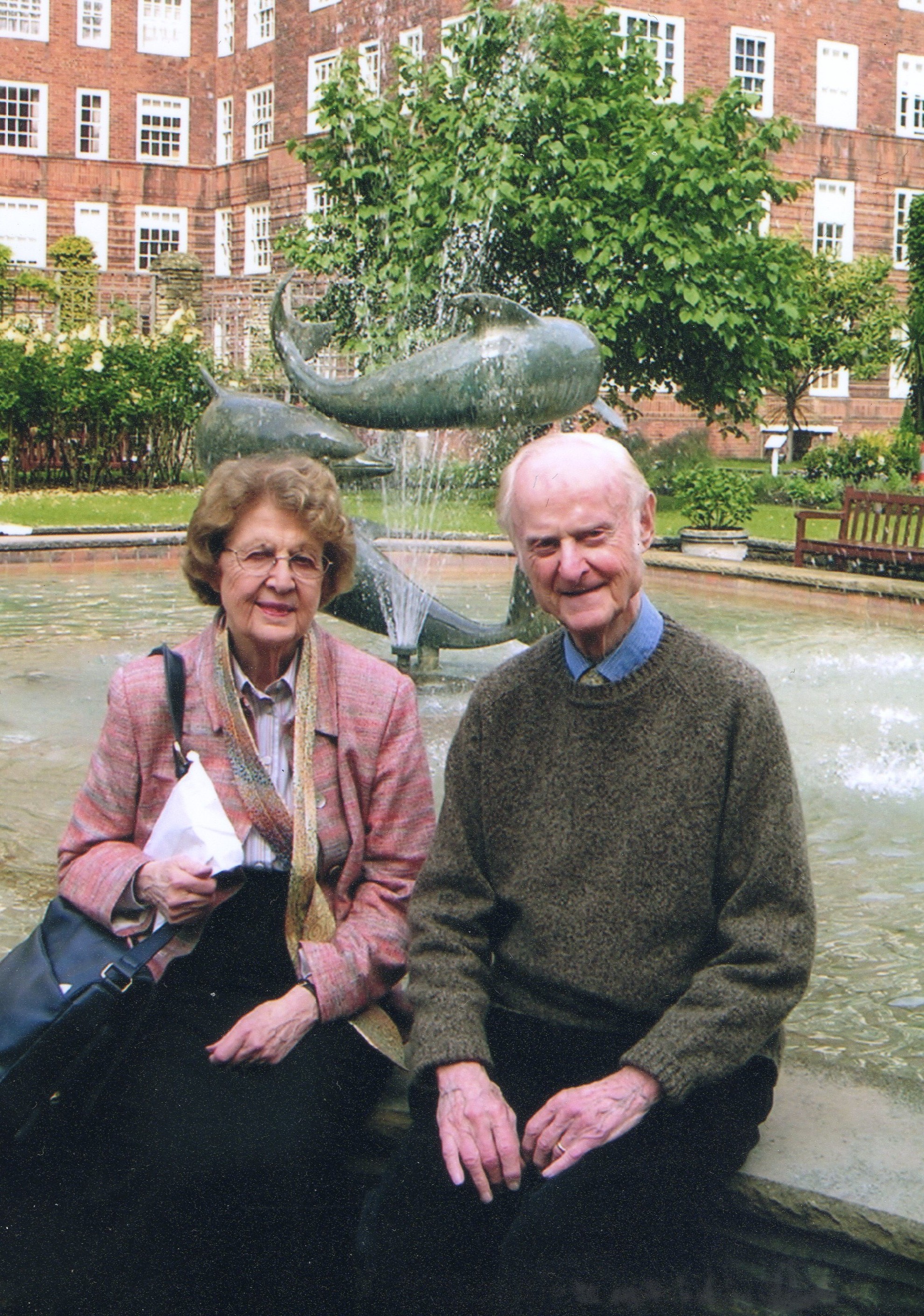

Family

He married author Elaine "Mac" Macmann Willoughby in 1957. He had known Mac, who is the children’s author Elaine Macmann, from his time at the New England Conservatory. They saw one another occasionally over the years, and in the summer of 1957 they decided they were the right people for each other. They first met at a church group in Boston while she was teaching in Norwood and Bob was at the New England Conservatory. After they married, they lived mostly in Oberlin until 1987 when they moved to New Castle, NH. They spent one year in Cincinnati in 1960 where Bob took a break from Oberlin. While in Cincinnati he was First Flute for the Cincinnati Orchestra and their son John was born. The following year they returned to Oberlin.

Summers were spent at various flute programs, largely in New England, but much of their time was spend in New Castle, NH where Bob played in the orchestra at the Wentworth By The Sea - a grand old New England resort hotel. The family had the run of the facilities there so it was a bit like being paid to go on vacation.

They also spent several years in London where Bob spent sabaticals researching barouque flute. Bob and Mac (and John) fell in love with London and returned frequently on vacations, usually staying at their favorite Dolphin Square

Fast forward - John married Bonnie and they had Courtney, Chelsea, and Colin. Bob and Mac enjoyed spending time with the extended family and even going on a number of trips all together.

Mac died in 2012 and is buried in New Castle, NH. Bob remained a frequent visitor with the rest of the family, and even went on several trips to London with John and Bonnie. Bob died on March 27, 2018 at the age of 96 and is buried next to Mac in the Oceanside Cemetary in New Castle, NH

Find out more about his funeral.

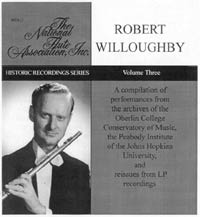

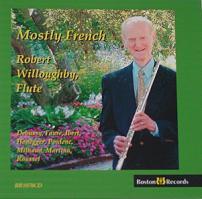

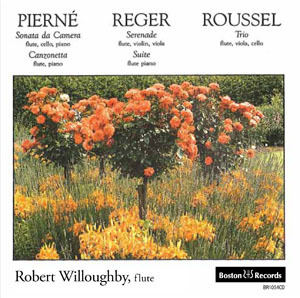

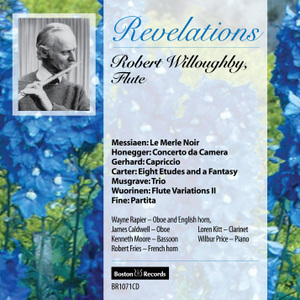

CDs available for purchase

Selected discography

He has recordings released on Gasparo, Vox, CRI, Coronet, Boston Records, and the Smithsonian label.

Solo Recordings

- Flute solos. OMEA Contest List Recording, With Wilbur Price, pianist. Coronet Recording Co., Columbus, Ohio.

- Paul Hindemith: Sonata for flute and piano; Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Concerto I in G Major, Allegro Maestoso; Francis Poulenc: Sonata for flute and piano; Gabriel Fauré: Fantasie; Claude Debussy: Syrinx for flute alone.

- Flute solos. With Wilbur Price, pianist. Artist-in-Residence Series, Coronet Recording Co., Columbus, Ohio. LPS3006 [197-]

- Bohuslav Martinu: Sonata for flute and piano; Paul Hindemith: Acht Stücke für Flüte Allein; Edgar Varèse: Density 21.5; André Caplet: Reverie et Petite Valse.

- French flute frappé. With Wilbur Price, pianist. Artist-in-Residence Series, Coronet Recording Co., Columbus, Ohio. LPS 3005 [1976?]

- Darius Milhaud: Sonatine; Jacques Ibert: Pièce; Jacques Ibert: Jeux; Albert Roussel: Joueurs de flûte; Arthur Honegger: Danse de la chevre; Albert Roussel: Andante and Scherzo, op. 51.

Chamber Music

- For violin and piano/Bülent Arel. Piece for four/Olly Wilson. Terezin/Robert Stern. With Gene Young, trumpet, Joseph Schwartz, piano; Bertram Turetzky, bass. Composers Recording Institute CRI SD264 [1971]

- Olly Wilson: Pieces for Four

- Other pieces: Bülent Arel: For Violin and Piano; Robert Stern: Terezin.

- Frank Martin interprète Frank Martin. With Frank Martin, piano. Recorded in Hanover, N.H., June 28, 1967. Jecklin Disco JD 663-2

- Frank Martin: Ballade pour flûte et piano (1939).

- With: Sechs Monologe aus Jedermann; Drey Minnelieder; Trois chants de Noël; Eight Préludes for piano; Ballade for cello and piano.

- Max Reger. With Marilyn McDonald, violin; John Tartaglia, viola; Wilbur Price, piano. Gasparo GS-224, c. 1982.

- Max Reger: Serenade in G Major, op. 141A, flute, violin, and viola; Suite in a minor, op. 103a, flute and piano.

- National Contest List Recordings. Oberlin Faculty Woodwind Quintet: George Waln, clarinet; Wayne Rapier, oboe, Kenneth Moore, bassoon; Robert Fries, horn. Coronet Recording Company, Columbus, Ohio. #1408 850C-3650 (W4RS-3651)

- Stravinsky-Barrère: Pastorale; Mozart-Meyer: Andante; Hindemith: Quintet; Bach-Henschel: Sarabande in D Minor; Cambini: Quintet #3; Bozza: Scherzo.

- Oberlin Woodwind Quintet. Oberlin Faculty Woodwind Quintet: Lawrence McDonald, clarinet; James Caldwell, oboe; Kenneth Moore, bassoon; Robert Fries, horn. Gasparo GS-204CX

- Arnold Schoenberg: Quintet for Wind Instruments, Op. 26.

- Robert Willoughby, flutist. With Marilyn McDonald, violinist; John Tartaglia, viola; Wilber Price, piano; Kathryn Plummer, viola; Catharina Meints, cello. Gasparo Gallante GG-1003. Reissue from GS-224 and GS-244

- Gabriel Pierné: Sonata da Camera, Op. 48 and Canzonetta; Max Reger: Serenade in G Major, Op. 141A; Suite in a minor, Op. 103A; Albert Roussel: Trio, Op. 40.

- 3 pieces for violin & electric piano. Proportions, for nine players. Duo exchanges, for clarinet & percussion. 5 pieces for piano. Music of Wendell Logan. With Richard Young, violin; Lawrence McDonald, clarinet; Gene Young, trumpet; James Roosa, trombone; Dianne Cooper, violin; Aaron Henderson, violoncello; Michael Rosen and Andre Whatley, percussion; Wilbur Price, piano; Kenneth Moore, conductor. Recorded in Warner Hall, Oberlin Conservatory, Oberlin, Ohio, January-May 1979. Orion ORS 80373 [1979]

- Wendell Logan: Proportions for nine players.

- The Oberlin Woodwind Quintet, Robert Willoughby, flute James Caldwell, oboe Lawrence McDonald, clarinet Robert Fries, french horn Kenneth Moore, bassoon Saturday, January 14, 1984 8:00 p.m. in Hamman Hall, Rice University Digital Scholarship Archive http://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/76867

Orchestral Music as Principal Flute

- Symphony. By Peter Racine Fricker. Recorded live by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Max Rudolph, conductor on October 16, 1959 in Music Hall, Cincinnati, Ohio. First United States performance. Recorded and distributed by the Recording Guarantee Project, American International Music Fund, Koussevitzky Music Foundation.

- Symphony No. 1. By Josef Tal. Recorded live by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Max Rudolph, conductor on February 12, 1960 in Music Hall, Cincinnati, Ohio. First United States performance. Recorded and distributed by the Recording Guarantee Project, American International Music Fund, Koussevitzky Music Foundation.

- Verses from a children’s book. By Samuel S. Ensor. Recorded live by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Max Rudolph, conductor, Charlotte Shockley, narrator, on February 13, 1960 in Music Hall, Cincinnati, Ohio. First United States performance. Recorded and distributed by the Recording Guarantee Project, American International Music Fund, Koussevitzky Music Foundation.

- Robert Willoughby may also be heard on numberous recordings as assistant principal flute of the Cleveland Orchestra from 1946 to 1955.

Baroque Flute

- Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767). The Oberlin Baroque Institute, Oberlin, Ohio. (1981) August Wenzinger, director. With August Wenziner, and Catharina Meints, viole da gamba. Gasparo GS-228

- Georg Philipp Telemann: Quartet in G major for flute, two violes da gamba and continuo, Darmstadt, MS. 1042/90.

- Others without flute:

- Georg Philipp Telemann: Sonata in a minor for oboe and continuo from Der Getreue Musik-Meister, (1728-29); Sonata in e minor for viola da gamba and continuo from Essercizi Musici (c.1720); Cantata: Du aber Daniel, gehe him.

- G. F. Handel: Eight Sonatas for Diverse Instruments. Smithsonian Chamber Players, James Weaver, artistic director. Recorded in the Coolidge Auditorium of the Library of Congress, Washington, D. C., May 18-21, 1981 on original instruments. Smithsonian Institute N029C

- G. F. Handel: Sonata in B minor for violin, flute and continuo; Sonata in B minor for flute and continuo.

- G.F. Handel: Opus 3, Seven Concerti Grossi. Smithsonian Chamber Players, James Weaver, artistic director. Recorded in the Coolidge Auditorium of the Library of Congress, Washington, D. C., August-September 1979 on original instruments. Smithsonian Institute N 023C

- G. F. Handel: Concerto III in G Major.

- Masterpieces of the French baroque. Oberlin Baroque Ensemble: Marilyn McDonald, baroque violin; Catharina Meints, viol; James Caldwell, viol and baroque oboe; Lisa Goode Crawford, harpsichord, leader. VoxBox 3 CD3X 3006.

- Reissue of Music of the French Baroque, Vox SVBX 5142 [1975] with additional literature.

- Joseph Bodin de Boismortier: Sonata in G Major for flute and obbligato harpsichord, op. 91.

- Others without flute:

- François Couperin : Pièces en concert for cello and strings; Louis Couperin: Five Symphonies for viols and basso continuo; Sieur de Sainte-Colombe: Two Concerts for two bass viols; Marin Marais: Suite in B Minor from Book II of Pièces de violes; Marin Marais: La Gamme; Joseph Bodin de Boismortier: Don Quichotte chez la duchesse; Marc- Antoine Charpentier: Suite for string orchestra; François Couperin: Sonade en trio “La steinquerque”; Jean Barrière: Sonate No. IV in G Major for violin and basso continue, Book V; Jean-Philippe Rameau: Deuxième concerto from the Pièces de clavecin en concert; François Couperin: Sonade en Quatuor, "La Sultane".

- Music of the Berlin Court. Oberlin Baroque Performance Institute, Oberlin, Ohio. (1980): Michael Lynn, recorder, James Caldwell, viola da gamba and Lisa Goode Crawford, harpsichord. Gasparo GS-220 Franz (Frantisek) Benda: Trio Sonata in C Major, flute, recorder and Continuo. Others without flute: Franz (Frantisek) Benda: Sonata in A Major, violin and continuo; Johann Gottlieb Graun: Cantate "O Dio, Fileno".

- Music of the French Baroque. Oberlin Baroque Ensemble: Marilyn McDonald,

baroque violin; James Caldwell, viol and baroque oboe; Lisa Goode Crawford,

harpsichord; Catharina Meints, viol. Vox SVBX 5142 [1975]

- Joseph Bodin de Boismortier: Sonata in G Major for flute and obbligato harpsichord, op. 91.

- Others without flute:

- Louis Couperin: Five Symphonies for viols and basso continuo; Sieur de Sainte-Colombe: Two Concerts for two bass viols; Marin Marais: Suite in B Minor from Book II of Pièces de violes; Marin Marais: La Gamme; François Couperin: Sonade en Trio: "La Steinquerque"; Jean Barrière: Sonate No. IV in G Major for violin and basso continue, Book V; Jean- Philippe Rameau: Deuxième concerto from the Pièces de clavecin en concert; François Couperin: Sonade en Quatuor, "La Sultane".

- Trio Sonatas of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach . Oberlin Baroque Ensemble: Marilyn McDonald, baroque violin; James Caldwell, baroque oboe and viola da gamba; Catharina Meints, viola da gamba and baroque violoncello; Lisa Goode Crawford, harpsichord. Gasparo GS-209CX

- C.P.E. Bach: Trio Sonata in D minor for flute, violin and continuo, Wq 145.

- The 250th Commemoration of Marin Marais. The Oberlin Baroque Ensemble with August Wenzinger and James Weaver. Gasparo GS-202

- Marin Marais: Pièces en Trio in E Minor (1692).

- Others without flute:

- Pièces à Trois violes (in G Major), from Livre IV; Pièces a une et trois violes (1717); Pièces de Viole d'un gout Etranger from Livre IV; Sonnerie de Ste. Genevieve du Mont de Paris (1723).

Publications

- "The Flute Practice Techniques", Conn-Selmer Keynotes, 1974.

- And many others that I need to add here...

Further reading and listening

- Robert Bigio (December 2010). Robert Willoughby: American Grandmaster of the Flute. Flute.

- "NFA Achievement Awards". nfaonline.org.

- Will Mason (2011). Former Professor of Flute Robert Willoughby Celebrates 90th Birthday. Oberlin Conservatory Magazine, 2011.

- "Conn-Selmer Keynotes". conn-selmer.com.

- Robert Willoughby. Faculty at Longy School of Music.

- Robert Willoughby. Rochester University Alumni Profile.

- Robert Willoughby. Boston Records.

- “Robert Willoughby – Seeking Variety” (interview with William Montgomery). Flute Talk (October 1984): 2-6.

- “Robert Willoughby: Combining the Best of Schools” (interview with Kerry Walker). Flute Talk (December 1994): 8-10.

- "From Mariano and Kincaid to Decades of Fine Teaching" (interview with Vanessa Mulvey and Vanessa Holroyd). Flute Talk (February 2001): 18-20

- Jictoria Jicha, "Robert Willoughby Combines the Wisdom of Three Masters". Flute Talk (November 2003): 4-11.

- Leonard L. Garrison, "Happy Birthday, Bob: A Tribute to Robert Willoughby" The Flutist Quarterly XXVI (2, Winter 2001): 57-61

- Leonard L. Garrison, "90th Birthday Celebration for Robert Willoughby". Flute Talk 31 (4, December 2011): 12-13

- "A Conversation with Robert Willoughby" (interview with Patricia George). Flute Talk 31 (4, December 2011): 14-17

- Aralee Dorough, "Robert Willoughby: The Next Decade". The Flutist Quarterly XXXVII (4, Summer 2012): 30-33.

- "Robert Willoughby, Noted Traverso Teacher, Feted at Oberlin". Early Music America 18 (3, Fall 2012): 39

- "Robert Willoughby", The Growing Bolder Radio Network (June 22 2014)

- Leela Breithaupt, Katherine Borst Jones, "Robert Willoughby 95 Lessons". Flute Talk 36 (September 2016): 24-27

- "The Gift of the Gold Flute".Crescendo.